1.

A good looking, long haired young Englishman, an SLR camera slung casually around his neck, sits dramatically astride the ridge of a zinc roof.

‘This is the roof of the Mathematics building’ he explains. ‘Inside the building at the moment … there is a revolution. About 100 or 200 students have barricaded themselves inside this building in order to repossess what they believe they ought to own … themselves. The right to determine their own future. Tonight this building will be liberated by the police force of New York City. The students no doubt will be hurt, fined, imprisoned, suspended, and certainly their careers will be compromised by the decisions and acts of this week’.

This film extract doesn’t show events this month (April 2024) at one of the Universities in the US where the police have been called in to clear camps of student protesting about their university’s investments in companies supporting the Israeli government’s war in Gaza. The sequence comes from Peter Whitehead’s 1969 film The Fall and shows students at Columbia University protesting against about the way that their university was profiting from the Vietnam War and using predatory real estate practices in neighbouring Harlem.

The students had accepted Whitehead as part of the occupation because of his track record as a radical filmmaker and he became a participant observer in their protest. The Fall includes some gruesome footage of the brutal and bloody way that the NYPD dealt with the students’ occupation.

Shocked by what happened, Columbia University created new mechanisms for facilitating peaceful student protest and decided that in future they would not use the NYPD to deal with protests. In April 2024 Columbia’s president Minouche Shafik overturned this precedent. Photos and videos of NYPD arresting students this April strongly recall the footage that Whitehead had filmed outside the same buildings 56 years earlier. Vietnam then, Gaza now. In both instances, Columbia students were, as Whitehead put it, claiming the right to determine their own futures.

Adam Tooze, who is a professor at Columbia, notes that his University is suffering huge reputational damage. He points out that the financial divestments that the students have, since October 2023, been calling for the University to make, amount to a tiny amount compared with Columbia’s huge financial resources. Student tuition fees make up a little over 3% of the University’s annual revenue. Their biggest income source is externally funded medical research (Tooze 2024 Substack). Students and teaching just don’t count for much in the neoliberal university.

2.

Back in 1968 when Whitehead predicted that, as a result of the University calling in the police, the students would be hurt, fined, imprisoned, suspended, and their careers would be compromised, he was pointing out that they were putting their collective struggle for a better society ahead of individual self-interest.

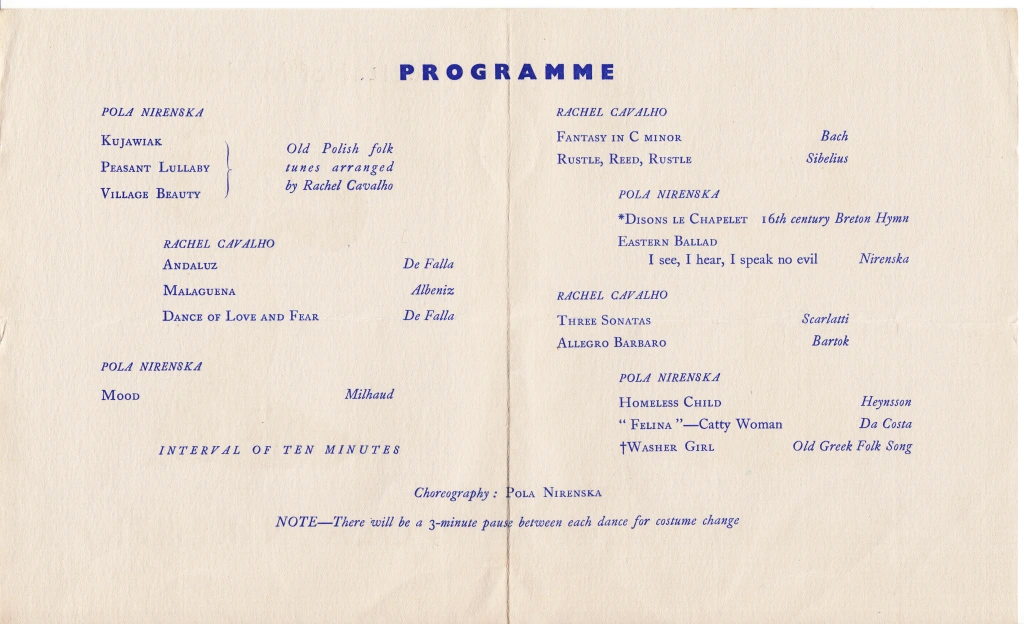

Whitehead was speaking as part of a revolutionary community. On the evening before the NYPD broke into the Mathematics Building, Whitehead filmed the students dancing. A feeling of community is one of the experiences that dancing can generate and this is what the students’ dancing does here. The first student in this scene with whom the camera engages, kicks off her shoes and to dance. She is not with a particular partner but is one of a loose group. Their movements are not set but improvised in an informal, spontaneous way that allows them all to bounce lightly along to the musical beat in an inclusive way. Their dancing, in effect, expresses communal values.

The students must mostly be in their early twenties, born in the late 1940s while their parents would have been born in the 1920s or earlier. These students are dancing in a very different way from their parents. Rather than dancing cheek to cheek in heterosexual couples, they are moving together in loose groups. The movements of their dancing ,and the music which they’re dancing to, derive from African diasporic cultural traditions.

Eldridge Cleaver, in a beautifully polemic essay published in 1969, describes the twist as

a guided missile launched from the ghetto into the heart of suburbia. The Twist succeeded, as politics, religion and law could never do, in writing in the heart and soul what the Supreme Court could only write on the books. (Eldridge Cleaver, The Soul on Ice)

While the students are not exactly dancing the twist, their movements are much more African in quality than the sorts of movements their parents would probably have danced. These aspects of the students’ partying add to our knowledge of the contingent, short-term community of which Whitehead was a part, and the revolutionary break it was making with the more restrained values and behaviour of an older generation.

For the soundtrack, Whitehead has used P.P. Arnold’s song ‘Everything’s gonna be alright’.

HEY, HEY, HEY. Everybody’s gonna say that everything’s alright.

‘Cos if they don’t, then boy there’s gonna be a fight.

I got a little things for you,

it’s all I got and it’s nothing new …

Everybody’s gonna say that everything’s alright.

Dancing to this song, while the police are shown massing outside, conveys a message of hope and resilience.

3.

In April 2024 as I watch posts on social media of police manhandling students on American campuses, I am outraged but at the same time feel hope in the protestors’ resilience. There is music or drumming in some of the clips and I like to think some dancing in the protest camps. The international attention these protests have attracted uncovers some of the contradictions of the neoliberal university. It raises questions about why students and their capacity for critical thinking are so threatening to the senior management of universities today. It shows that it is possible to challenge the power relations underlying the political economy of the university sector.

The sight of these protests gives me hope. Wendy Brown argues that capitalism in its current form assumes that individuals, working in a competitive environment, will make rational economic choices and ‘entrepreneurialize’ themselves as individuals (The Dig podcast). What I see today, however, are people putting a collective struggle for the progressive values they believe in ahead of the selfishly individualistic way it is presumed they will behave.

References

Brown, Wendy (2020, October 24) Ruins of Neoliberalism with Wendy Brown. Podcast: The Dig. (Accessed 29 April 2024). Available from https://thedigradio.com/podcast/ruins-of-neoliberalism-with-wendy-brown/

Cleaver, Eldridge (1968) Soul on Ice. New York : McGraw-Hill

The Fall (1969) Director: Peter Whitehead, London: Lorimer Productions.

Tooze, Adam (2024, April 26) Chartbook 279: Columbia University’s “crisis” – a political economy sketch map. Blog: Chartbook. (Accessed 29 April 2024) Available from

https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/chartbook-279-columbia-universitys

Whitehead, Peter (2016) The Fall. A Screenplay. Hathor Publishing UK. Nohzone Archive.