Written in black pen on the DVD is ‘Interview with the Alien’ and in blue ‘for Ramsay’. A gift from Peter Whitehead who died in June, and who had donated his archive to De Montfort University. On it is a film that documents a ballet performance. At the beginning, after the film’s name, is the subtitle ‘The hieroglyphic language of dance’ and at the end ‘The Petrograd State Ballet 1923’.

Whitehead was a writer and film maker probably best known for documenting the counterculture in London and New York in the 1960s and for pioneering promotional film clips for television for pop groups like the Rolling Stones and Pink Floyd.

Whitehead’s 1969 film The Fall contains documentary footage he filmed inside a student occupation at Columbia University and of its brutal suppression by the police.

When shown in a Greek film festival in 1973, it inspired student occupations in Athens that ultimately forced the military junta to cede power, leading to the restoration of democracy in Greece. I had heard about Whitehead from colleagues who are working on the archive, and knew that recently he has been writing novels. But, until I received the DVD from him, I had no idea he had also been involved in dance.

When I watched the video I didn’t know what to make of it and drew a blank when I showed it to friends who know more about ballet than I do. I had evidently been set a puzzle. I said this to Whitehead when I met him for the first and only time at the official launch of his archive, and asked for a clue. Have you ever heard of Guido Carmelich? he asked. I had but couldn’t immediately remember in what context.

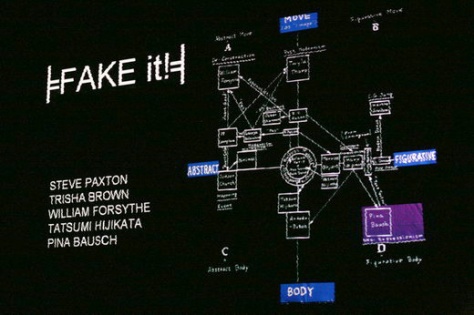

A search reveals that Carmelich is one of the choreographers whose work is presented in the Slovenian director Janez Janša’s 2007 work Fake It! which included unauthorised versions of famous works by Pina Bausch, Trisha Brown, William Forsythe, Tatsumi Hijikata, and Steve Paxton.

When the piece went on tour internationally, the company wanted to add a work by a Slovenian choreographer and decided to revive Carmelich’s 1960 solo Monument for an Unknown Dancer.

The programme for Fake It! explains that Carmelich had been an intern with Béjart in Brussels in 1960 when the latter was making his much acclaimed version of Le Sacre du Printemps. Béjart and Carmelich, it explains, ‘shared a common view that dance should be less formalistic and based on developing moving potentials of each individual’. Béjart named his dance group Ballet du XXeme Siècle. ‘Carmelich argued that the name should be Ballet du XXIeme Siècle because, to him, the C20th represented the defeat of the humanist ideal and he didn’t want to associate his art with historical experiences of exploitation, wars and catastrophes’. The two went their separate ways.

Whitehead told me that he met in Carmelich in New York when he was filming The Fall, and invited him to make a cameo appearance in it. Carmelich is shown dancing in a subway car with the iconic 1960s model Penelope Tree.

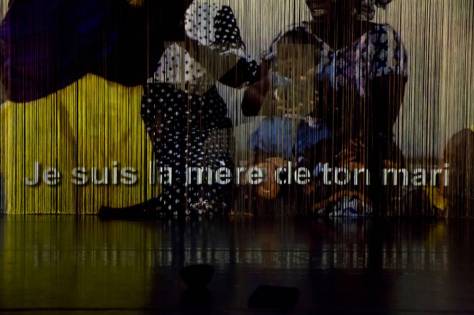

In the early 1970s Carmelich was commissioned to make a new work for the ballet company at the National Theatre of Belgrade. The theme that the commissioning committee gave him was a materialist view of historical development based on a famous debate in St Petersburg in 1923 between Anatoly Lunacharsky, People’s Commissar for Education and Culture – the Politburo member who invited Isadora Duncan to start a school in Moscow – and the writer Maxim Gorky, exemplar of the socialist realist novel.

Marx had argued that, in any historical period, social relations are determined by the relations of production:

It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness. At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production […] Then begins an era of social revolution. (A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, 1859)

Gorky and Lunacharsky, having just attended a performance by the Petrograd State Ballet, debated its relevance for the revolution.

Gorky argued that ballet was not capable of supporting the historical destiny of the proletariat in revolutionary class struggle. Lunacharsky, however, argued for the cultural importance of ballet as an art form and proposed that the ballet of the future would convey ideas not yet conceivable in words.

Carmelich told Whitehead about his commission when they met by chance in the Egyptian galleries in the Louvre, both sharing a fascination with Egyptian art. Together they came up with an interpretation of what Lunacharsky meant when he said that dance was hieroglyphic. Like dance, a hieroglyph is and is not a language. It inscribes sufficient information that is at times an extension of language, at times in opposition to it, but the one always in relation to the other even if in a contradictory way.

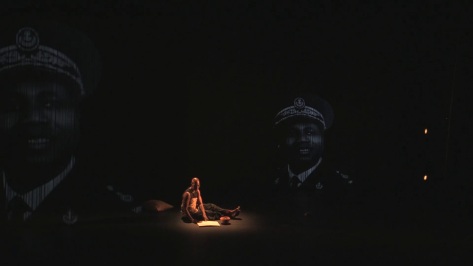

They then developed a story line for the ballet about a visitor from another planet – The Alien – who could understand, through reading the hieroglyphics of dance, the relation between the modes of production and the material productive forces of society. The Alien had only been allowed to see this, however, on condition that she didn’t interfere in the historical process however much she wanted to accelerate society to the point where social revolution and cultural renewal could occur.

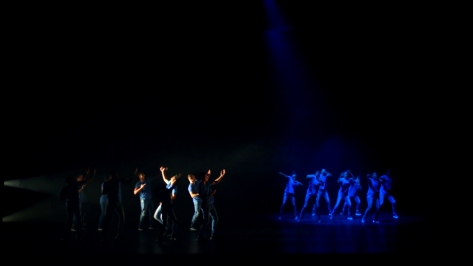

Carmelich and Whitehead wanted the extra-terrestrial beings in the ballet to be modelled on figures in Egyptian mythology, in particular the trinity of Osiris, Isis, and Horus. The Alien, they decided, should be costumed as the Falcon-headed god Horus. There were even discussions about whether the artist Penny Slinger, Whitehead’s former partner, could design these costumes. Slinger and Whitehead both shared a fascination with falconry and Egyoptology. This idea, however, proved to be unacceptable to the committee in Belgrade, so instead the extra-terrestrials in the ballet wear C18th century periwigs, while different stages of historical development are represented by different costumes – the white faced, clown-like group, the Coryphées in black tunics and grey tights, and the group of soloists in bright coloured leotards or jeans. The pas de deux between the male extra-terrestrial – wearing a frilly, pale blue eighteenth-century frock coat and periwig, and the Alien – in white tights and periwig –reprises Carmelich’s duet with Penelope Tree in The Fall.

For some reason, the committee in Belgrade wanted the piece to be set to music by Mozart, but here Carmelich, having given way over Horus, insisted on using a recording of piano music that Whitehead had composed, based on his music for Daddy, his 1973 film made in collaboration with the artist Niki de Saint Phalle.

Interview with the Alien, which premiered in Belgrade in 1975, was an immediate success and won a special commendation when shown at Bitef, Belgrade’s International Theatre Festival later the same year, (the Grand Prix that year going to Tadeusz Kantor’s The Dead Class).

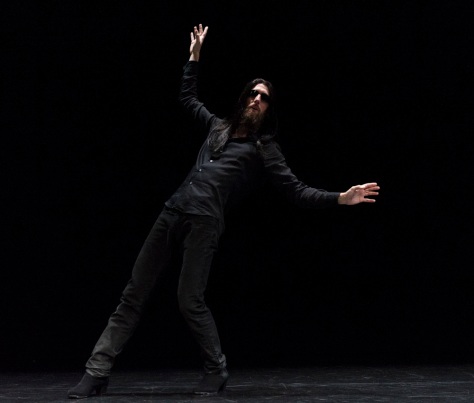

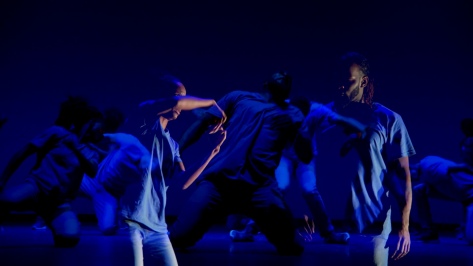

In the closing moments of the ballet, The Alien’s solo evokes Horus’s flight across the sky. Horus was considered to contain the sun and moon. The sun was his right eye and the moon his left, and they traversed the sky when Horus, as a falcon, flew across it. Carmelich told the commissioning committee that this final choreographed sequence represented the entirety of the historical process condensed into a single day, so that the Alien’s final kiss to the audience represents the dawning of the new morning of the revolution.

This solo with its delicately poised, strutting steps and staccato shifts of the neck and head, make The Alien strangely bird-like. Whitehead explains that the falcon’s piercing gaze, rather than representing a Marxist understanding of history, signified for the two of them a burning desire for the social, cultural, and spiritual renewal that they both longed for.